Mysterious in origin, a virus has spread across rural Quebec. The people infected have become zombies who roam the countryside or stagnate there, waiting for their next carriers. What are their intentions? Bite some arteries. Spread the virus. Infect the few healthy left. Oh, yeah. And steal furniture. This is the premise of Robin Aubert’s zombie film, Les Affamés (2017).

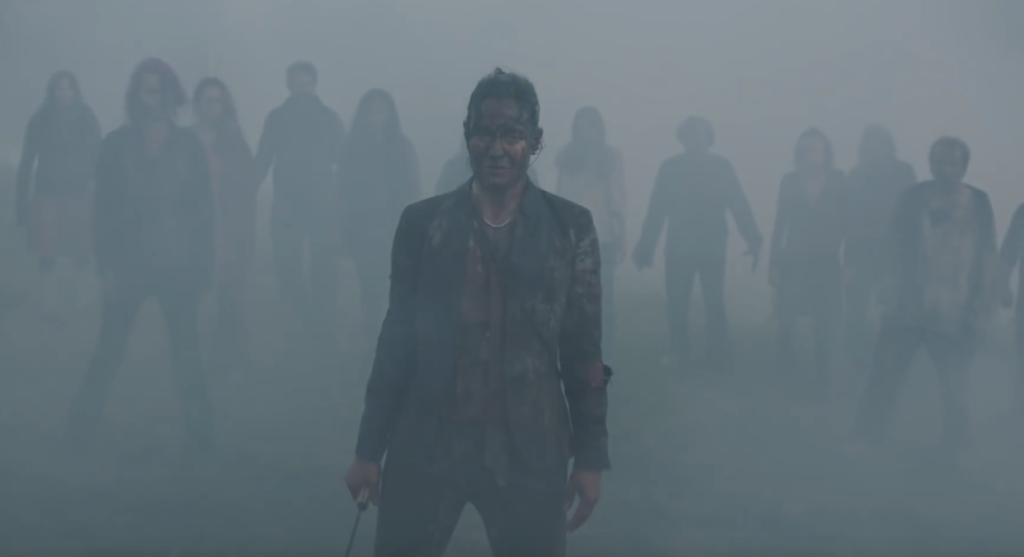

Viewers can expect some familiar tropes from the horror sub-genre: Aubert’s zombies must bite an uninfected person to transmit the virus. The zombies inherit an extraordinary ability from the virus—hypersensitivity to sound. They have discoloured skin. They search for new hosts in packs. They sprint non-stop. They snarl, and they scream. Mostly, they’re plain pissed off. As far as trope-y zombie-horror settings go, a fog billows over a deserted rural municipality of Quebec. There’s a discharged military man traveling a highway who keeps popping up on our protagonists, bent on jump-scaring them for kicks.

Aubert’s vision may not rely on as much gore as other directors’, but there’s still plenty of bloodshed. Open wound tissue looks realistic enough to induce nausea (for me, anyway). Blood leaks in crimson or blood splatters against different glass surfaces. Much later into the film, there’s this one stunning yet evil shot of filthy zombie arms holding their hands up to projectile blood where that stream of blood flows straight-up and back-and-forth in the way that lawn sprinklers do. A chunk of a main character’s ear dangles near her cheek. A decapitated body falls over, so that the mangled depth of a neck’s wet muscle is exposed.

However provincial, the setting seems post-apocalyptic for all its disarray. A few shots in, the camera pans from a messy trail of plastic toys on a long, grey highway to an overturned vehicle. An old man enters the frame, gasping, as he catches his breath before running into the woods. He escapes a line of zombies chasing him. The film’s plot revolves around the hardships of survivors.

The plot follows the lives of many different characters. They struggle to survive in a lush yet barren Quebec. Its shade of green is depressing. Moreover, these characters are not one-dimensional. They are each mature, distinct, and fleshed out (pun intended). I watched the French version of the film, and although I took French until eighth grade, I’m not bilingual, so it was impossible for me to gain a perspective on the characters by listening to their words. But the basic plot doesn’t require dialogue to make sense of it. (Isn’t this true of many zombie movies, where the main point is to escape? I don’t know.) Tense exchanges, raw emotion, and defeatist silence all contribute to the dismal atmosphere that tinges their hopes of getting out of the province alive.

Spectacle-wearing, observant Bonin (Marc-André Grondin) and his jolly friend of colour, Vézina (Didier Lucien), trade some banter as they hop in Bonin’s truck. The truck roars to the right, out of the frame, and in its absence smoke rises from a zombie corpse. They’ve burned it. They’re giddy about having dodged the virus. For a while, they continue driving down a minor highway. Vézina signals Bonin to stop the truck. A shot-reverse-shot pattern shows a teenage girl and her little sister holding hands, down a clearing that leads sixty metres into a forest. It’s not that Vézina investigates. It’s that he’s lured. Some of the zombies are smarter than average. A few of them are even devious. Vézinagets bitten in the neck. At the same time, he shoots the smiling teen girl zombie who bit him. Les Affamés is very much a film of wrong turns and blocked paths.

Cut to Bonin and Vézina lying in the back of the truck. They’re looking up at the sky and discussing what the clouds look like (I think.) Vézina’s injury is so severe that he skips changing into a zombie and dies by bleeding out. Why are the black friends always the first to die? (Joking! But that’s a horror trope, right?)

Viewers have complained that Les Affamés is slow. As characters diverge on their routes or backtrack on them, eventful encounters hesitate to happen. Bonin drops by a random cabin, as he no doubt plans on burning Vézina’s body. There he discovers a woman tied to a bedpost in the cabin. After speaking to her, leaving her, and then having a change of heart about leaving her behind once he hears a zombie screaming in the woods (the zombie screams are sonically detailed—both crystal clear and guttural because of a double layering), he unties the damsel in distress. Is there romantic relationship potential here? Hardly. Tania (Monia Chakri) is suppressed. Bonin is detached. B. and T. freeze near the truck. (Bonin had already offloaded Vézina’s body, at least.) The key in the ignition chimes. B. and T. anticipate a response from the zombie who resides somewhere unseen in the woods.

As B. and T. drive away, they get company. A zombie jumps onto the truck and sticks its head through the back window. Terrified, Tania blows its head off with a shot gun. She gets blood on an accordion she’s brought along. After riding passenger side, as she and Bonin go nowhere fast, Tania reaches into the glove compartment for a map. She uses the map not to plan a route but to wipe her accordion clean. Tania’s using the map as a napkin and Bonin’s casual glances at her doing so nicely indicates their dejected attitude.

At the same time, there’s a subtle message about consumerism that Les Affamés concerns itself with. Given that I don’t understand French, the most critical thematic thing I notice are the images. Aubert’s scenes play out to me like a photo essay or a visual meditation on the greed of contemporary consumerism:

After B. and T. have adopted a little girl from an empty house, to make sure they won’t draw attention from any lurking zombies while they drive alongside a field, Bonin investigates a farm house at a turn up ahead. He looks behind the house. Sure enough, zombies. They’re dispersed over the open field. They’re silent, standing before a mound. Spaced-out wooden chairs surround the mound. A left-to-right camera tracking shot shows a T.V. set, chains, boots, poles, rustic things, and lots of junk. The zombies have accumulated a wealth of items—household items. Even weirder, it seems that the mound has put them under a trance, a trance of… Satisfaction? Fascination? Hypnosis?

It’s not that when the zombie attacked the truck he was singly interested in infecting B. and T. He also wanted to steal the truck and/or whatever items were inside it.

Meanwhile, the old man from an opening shot of the film slumps to a tree trunk, having given up his evasion of zombies. His leg is wounded. It seems like he’s done for. But a boy with a rifle comes to his aid and blows off one of the zombie’s heads and then double-taps the other one. A flashback shows the boy aiming a rifle at his own mom, who, bitten, rocks back-and-forth on a rocking chair on the front porch of her house. He and the old man team up, after the old man ties a bandage around his own leg and fashions a walking stick.

A woman in business attire (Brigitte Poupart) sits in her car with the front door open, on the main street of an empty town. She blares the radio. The noise attracts a straggler zombie. It’s running toward her. Composed, she picks up a meat cleaver resting in her console. She confronts the zombie at her Mercedes station wagon’s back window. Blood splatters against the window as she viciously hacks the zombie to death. In the aspect of blood splattering against glass, this shot bears a resemblance to one of the opening shots of the film in which pressurized blood spraying from an artery drops against the glass of the camera, breaking the fourth wall. The woman in business attire, Céline, gets back into her station wagon and closes the door. In the medium shot, in the back of her car is a vacant car seat. A zombie kid stares at her through the driver side glass window, as she pulls away, symbolizing one of her own kids that she’s had to leave behind.

After some traveling, Céline arrives on an acreage. She’s seeking provisions. She finds a gas reservoir and lifts a nozzle from the equipment frame. As she lifts it up, guns cock behind her. Busted. Two lesbians command her to strip. Cut to a full shot of Céline stripped down to her bra and underwear, the two middle-aged lesbians looking down their rifles. This stripping is an interesting subversion of the male gaze, which reduces women to objects of sexual desire and gratification. We see Aubert’s insinuation of this in the previous shot where Bonin finds Tania in the bedroom with her hands tied and a gag in her mouth. In this case, the offender is not a male but two lesbian partners who are inclined to have a sexual interest in Céline. I understand the more straightforward reading might be that these women are administering a protective measure by making sure Céline has no bite marks or weapons already on her. However, this sensitivity to gazing or glancing or staring is undoubtedly a preoccupation of Aubert’s. Across a few different shots, there’s a prolonged focus on the back of a zombie, and then—suddenly attentive—the zombie turns around to encounter the stare with annoyance.

Once one of the lesbians sees the car seat, she deduces that Céline had a role as a mother, and graciously she absolves her. Cut to the three of them, each on a rocking chair on the front porch, each drinking a bottle of beer, subdued.

Bonin, Céline, and the little girl arrive at an acreage. Bonin storms out of the vehicle to the front door, where one of the lesbians slaps him. As it turns out, Pauline (Micheline Lanctôt), is Bonin’s mother so he got in trouble for leaving home without giving any notice of when he’d be back. (He also ignored his mom on their two-way radio, when she tried to contact him. That’s low.) Bonin soon joins Pauline and her partner, Thérèse (Marie-Ginette Guay), around the kitchen table where a map has been laid out. Céline is also there, of course. They all make a consensus decision about which route provides their best opportunity for escaping the encroaching zombie horde. Everyone comes to an agreement on the route. They all go to bed. Bonin and Tania share a bedroom. They make little progress on the romantic relationship frontier. Tania’s suppression and Bonin’s detachment continue. A high angle shot shows Bonin going to sleep with his glasses still on! Nothing says you’re out-of-touch with reality like wearing your glasses to sleep.

The very next day, when the group sneaks out the back door, a zombie crashes into the house, breaking and entering. It nabs a wooden chair.

The group sprints away from the house, toward tree cover. A crane shot moves over a sunlit forest of hundreds of trees. In what appears to be a shot highlighting the awesome magnitude of the tree canopy, disembodied zombie screams sound out at ten second intervals, making this shot spine-chilling. Here, Aubert has taken a page out of Alfred Hitchcock’s book. Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, suggests that a technique of Hitchcock’s was to film an establishing shot—an omniscient point of view—in which the neutral tone is abruptly interrupted by a malevolent figure, as if God’s omniscience was really malevolent underneath. I want to suggest that Aubert’s shot unfolds in much the same way. The shot tracks the forest passing below, neutrally, but instead of a malevolent figure turning up in the frame, it’s the audio clip of repeated curdling screams which interrupt yet underpin and nuance this shot.

The group reach the forest. They’ve alarmed the forest-dwelling undead, though. Carnage ensues. Céline goes apeshit. She runs around, on a zombie killing spree. In a sequence of shots devoted to her, she impresses with her passionate slashing, her energy, and her half-way insanity. It’s not much of a stretch to say that she has some demons. Personally, to me, Céline comes to represent Baba Yaga. Baba Yaga is a character of Russian folklore. She lives in a cottage in the woods, and if anyone finds her, those passersby either become her ally or her adversary, depending on her mood. In one version, she’s a cannibal who eats children that stumble onto her cottage. Although there are no overt references to Russia in the film, the mythical figure nevertheless remains. In a medium shot, as Céline stabs a zombie, she scowls. The scowl looks like the kind I’d express when I was young. I’d put my index fingers in each corner of my mouth and pull down diagonally before pointing my bottom row of teeth at someone. Her face extends and stretches at the jaw: Another attribute of Baba Yaga is deformity. Although Céline doesn’t eat any kids, she does end up murdering the little boy, at his discretion after he’s bitten by a zombie.

Céline leads a charge out of the forest. This running route seems to be their best means of escape. A baby cries from a fog-cloud on the prairie. Céline goes to investigate. It’s a zombie woman, cross-legged, pulling the string of a plastic baby doll. Céline and the zombie exchange glances for a while. The zombie shrieks. A gang of generic zombies emerge from the fog, pursuing the fleeing group of survivors, hot on their heels. Who has any will left to keep on running? Which members of the group give up? How much more treacherous can the path ahead get?

For everyone, there’s a time to push through and there’s a time to lie down and accept defeat.