Imagine one night going to sleep and dreaming about your upcoming sporting event, a meeting with an old friend or maybe you’re a student dreaming about a new chapter you were studying. Now imagine jumping from your bed to your feet, in the middle of the night to sirens, to bombs and bullets. When the Syrian war broke out, there was only time to run. It dispersed 6 million people that are currently displaced all over the world. This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Syrian Refugee Crisis. It is one of the largest human-forced migration crises of our time. As of 2020, stats show that our country welcomed 44,000 plus Syrian refugees, with 7,000 living in Toronto.

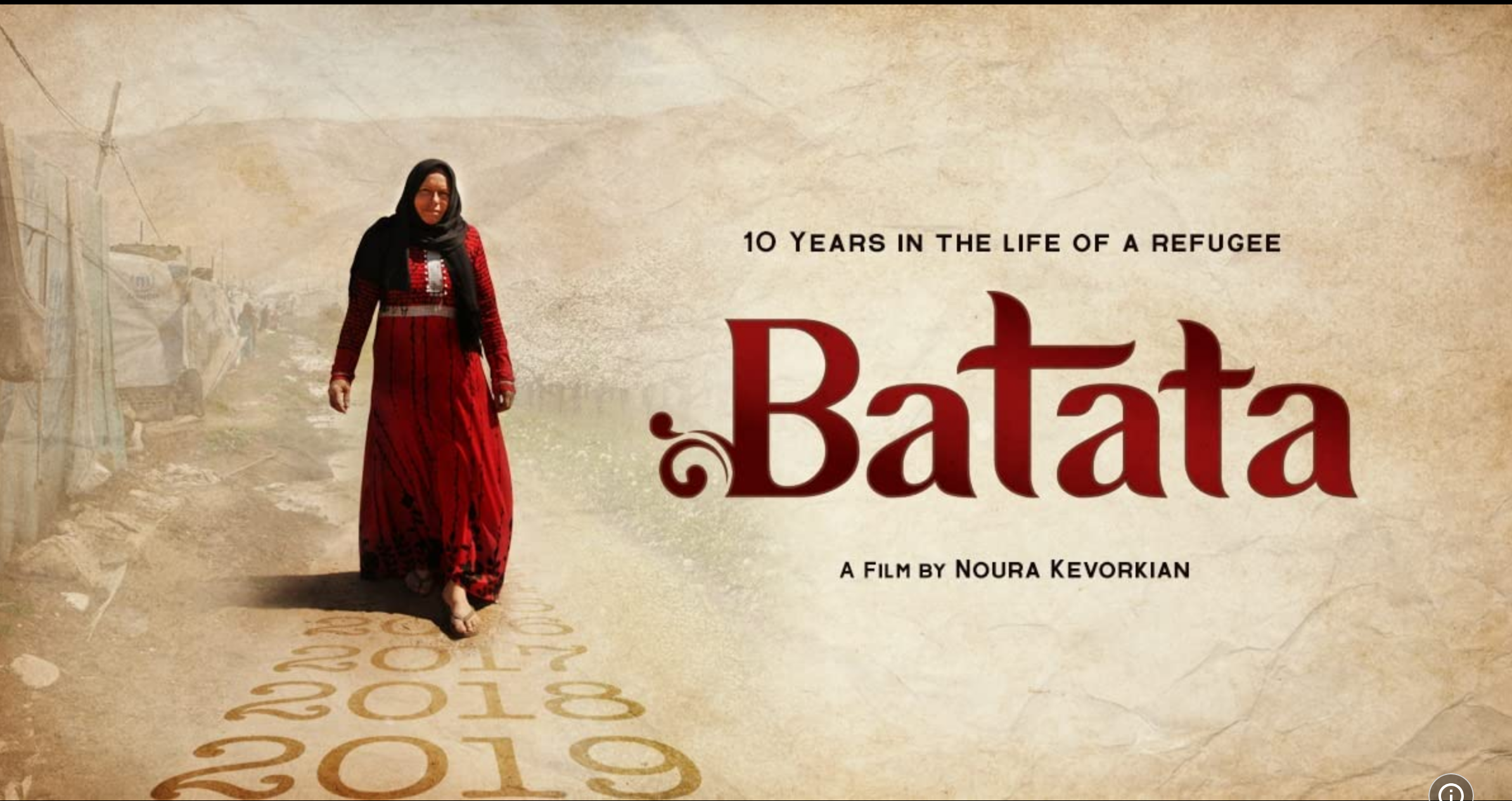

The feature documentary, Batata shines a light rarely seen on camera; from the perspective of a refugee. In 2008, Lebanese-Syrian filmmaker, Noura Kevorkian, was introduced to an unmarried Syrian woman named Maria, who was working in Lebanon, planting potatoes to support herself. Fascinated by her life, Noura began to film Maria as a documentary subject. When the Syrian war broke out, Maria was no longer able to return to her hometown, so she began to help her family escape to Lebanon. She transformed a flourishing potato farm into a safe haven for her extended friends and family seeking refuge from the war. The farm is currently home to one of the largest refugee camps in Lebanon today.

Nouras’ experience, over the course of the next decade, was one that came with a price. Being thrown into the depths of the Syrian war, she experienced PTSD for many years. Having lived in the tents with the refugees for weeks/months at a time; she experienced guilt as her camera captured the despair and sometimes anger directed toward her, because she had the ability to leave and return to Canada. When she was home she always felt the need to go back to try and help.

The film has made the list at this year’s Hot Docs and will have its North American premiere there. Given what is currently going on in Ukraine as one of the other largest refugee crises in the world, this film reflects a post-migration/diaspora as the next phase of fleeing a war-torn country and trying to survive the next day, then week and months. Noura has built a window into the crisis that lasted for 10 years. There are incredible stories throughout the 10 years and it is a love letter to the refugee community that became extended family and friends for the 10-year duration. War has long lasting effects with people and families being changed forever. It’s important to document these events, for the sake of history and to evoke change and compassion.

I had the great honour of speaking with Noura recently in regards to her film. It was extraordinary and really provided clarity for me. She’s made many sacrifices to tell this 10-year story of a refugee crisis and she deserves every accolade coming her way. It started off as a personal subject film and quickly took a turn. She rolled with it and the results are an incredibly impactful film, Batata. Roll the tape!

HNMAG “This film takes the audience on an incredible journey. What was your motivation to start filming?”

NOURA “In 2009, Batata started as a story about a Syrian farmer in Lebanon named Maria. She is a charismatic woman who supported her family as a migrant worker. Surprising to everyone, The Syrian revolution started and the film took a different narrative that none of us were prepared for. The film became a much larger story and a first-hand look at the lives of refugees and how they were surviving in the crisis for 10 long years. I had already invested a lot of time into my relationships with Maria, her family, her relatives, the people that came from Raqqa and the hundreds of refugees arriving weekly. It became a really big story, so I kept filming for 10 long years.”

HNMAG “How long of a duration would you stay every time you travelled there?”

NOURA “Between 2009-2014 I went out twice per year with my 2 children for 3-4 months at a time. Sometimes I would stay in the tents with the refugees and sometimes I would go to my parents’ home. It was a real commitment but I didn’t go into it with the intention of filming for 10 years – it just happened slowly over time. I was thinking that I would follow them around for a few months at most. As a filmmaker and a woman, doing the filming on my own in a refugee camp… I wasn’t prepared for the emotional and psychological toll that the film took on me over the years. At some point, I felt like it was my responsibility to show the world what these people were going through. Because these tents are small and access is difficult, I couldn’t bring a crew with me; I had to do it on my own – from camera, lighting, sound, directing, producing and the location. My backpack was full of camera equipment and I was carrying my tripod through the mud and filming. It was cold, it was rainy, there was open sewage… my tripod broke several times. It was very challenging and I experienced all their trauma and absorbed their pain, as a filmmaker.”

Noura tells her story with grace and renewed strength, as she describes the mass diaspora. She’s dedicated 10 years to travelling back and forth for months on end to provide a window into the ever evolving and ever discouraging living conditions. Noura thanks her husband and producer of the film, Paul Scherzer for taking care of the kids every time she had to go away. She says, “My husband is the best producer in the world, he supported me and my family throughout the duration of the film.”

HNMAG “How has it been received at festivals?”

NOURA “In January, it had its world premiere in France. From there, it went onto Greece and currently it’s in a competition in Brazil and will be in Munich after that. It’s having a wonderful festival run and will also be showing at Canadian venues, with a competition at Hot Docs. Because I wasn’t able to attend any of the festivals live, my daughter who’s 12 and soon to be13, wanted to pitch in and make a 2-minute presentation. It’s really heart-warming because this Batata film started the year she was born. She was 8-weeks old when I strapped her to my chest and flew to Lebanon. All of her life, she has known Batata (laughing), so in our family we always joke around and say “mommy’s” films are always dated by the kids’ ages (laughing).”

HNMAG “You had a few drone shots in the documentary. Did you rent one or bring your own?”

NOURA “Yes, I had to rent a cheap drone. I couldn’t afford much and it was all shot in an hour. It was a bit nerve wracking because we are at the Syrian border and the Syrian army is watching us from over the mountain. In Lebanon, you can’t shoot without a permit because it could be military. Luckily, I found a local person in the village to help me. We used the cell phone to record 6 shots without getting shot at (laughing).”

HNMAG “How did you know when you had finished capturing enough footage and had reached the end of the story?”

NOURA “In March of 2020, I was scheduled to go back but then Covid happened. Once I realized everything was locked down, I started editing massive amounts of footage and stopped filming. Having said that, I’m still in touch with Maria, her friends and her relatives. I want to go back to Lebanon this year to see my family, Maria and the camp. There are hundreds of people that I know/care about and I want to see what’s happening with them. My husband says, “please don’t film anymore” (laughing), but I don’t know if I can promise that.”

HNMAG “You showed incredible tenacity, extraordinary persistence and ambition making this 10 year film. We were able to see many changes in the families, through growth, through marriage and sadly, through the death of Mousa. Maria was hoping to get married. Did she eventually find a husband?”

NOURA “Maria is such a responsible person and such a leader, she takes care of everyone and although it’s always been a dream of hers to marry and settle down with a family, after all these years – she’s given up that it’s going to happen. Sadly, Maria and her family, along with 6 million Syrian refugees are scattered around the world and still need help.”

HNMAG “This film really provides a large window over the 10 years of what a refugee life looks like and how grateful we should be to live in a free country.”

NOURA “I always tell my children that we are so lucky to be Canadian. When you see and meet the hundreds of refugees whose dream it is to come to Canada, it’s their wish – it makes you very grateful to live here. When I spoke to Maria, she told me her father Abu Jamil had another stroke 10 days ago and is bed ridden. Her mom is on an oxygen tank, her brother is trying to escape to Europe again, a child has passed away, there’s no food, there’s no medicine, it’s an absolute humanitarian crisis. Half of me is always over there trying to help. As Canadians, we’re very good at helping others and we need to continue to donate money to UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) whenever we can; every refugee needs help.”

HNMAG “You captured it very beautifully and I still can’t believe you were a 1 woman film crew. You did a phenomenal job.”

NOURA “Thank you, that means a lot. I think the only way this film was going to be this beautiful and this powerful is if it was a 1 woman show because of the access I was able to have. As a woman, that turned out to be a high cost to me. Because I had to do it on my own, leave my children at home and go through the emotional and psychological trauma year after year after year, it demonstrates the toll on filmmakers and journalists that these stories take on them, especially over an extensive period of time. I really want to share that with other storytellers/filmmakers that are starting new projects, so they can better prepare themselves. There needs to be importance on having a support group while you’re away. I wasn’t prepared for it because I didn’t plan to make a refugee crisis film, it just kind of happened. I hope they can avoid the pain that I’m going through.”

HNMAG “You must have so much footage after 10 years of filming. Was it difficult to cut it down into 1 film.”

NOURA “For me, it was trying to figure out how to combine 10 years of footage into a 2-hour documentary. How do you cut out the amazing little girl that you fell in love with and her little brother? One of the sad stories that had happened in those years, was about a little girl that would carry her little brother around. The little boy was stung by a scorpion and died. This was one of 100 sad things that happened and when you start cutting away these people’s stories, you feel bad that you can’t put it in for others to experience. The tall Lebanese man in the film finally got married a month ago and I have pictures from his wedding. They couldn’t afford a big party because Lebanon is in a devastating economic situation, there’s no money in the banks, it’s all disappeared. The corrupt government has taken peoples savings, the banking system has collapsed. My hope as a filmmaker is to see people going to the film and experiencing what the life of a refugee looks like.”

In closing, Noura told me how the smiles, the hospitality and the refugees’ sweet disposition would not falter or fade. They would invite you into their homes and offer their last piece of food or last cup of tea, to make you feel welcome as they apologize for having to burn plastic to provide heat inside the tent. Batata is remarkable and a piece of the puzzle that helps to answer some hard questions while reminding everyone about the continuing refugee crisis and the need to continue support efforts through UNHCR.