My first exposure to Guy Maddin was a nearly subconscious one. The trailer for his semi-autobiographical feature My Winnipeg was among several in a 20-minute promo reel that played continuously on repeat at the North Edmonton Blockbuster where I worked back in 2009. I had been employed there long enough to tune most movie ads out as background noise that came with the territory, akin to air conditioner or the nearby highway traffic. Still, his trailer stood out among the more conventional Hollywood fare being advertised alongside it and it was enough for me to bookmark the experience, even if I never got around to seeing My Winnipeg (still haven’t).

Years later when I had relocated to Vancouver and had started to read up on Canadian Film History, Maddin was a name as sure to crop up as David Cronenberg or Anne Wheeler. It was in this phase that I became familiar with many of his classic titles like Twilight of the Ice Nymphs and Brand Upon the Brain! through sheer research osmosis. Still, his titles failed to make my often weekly rentals or nightly streaming queues.

It wasn’t until the Cinematheque announced a career retrospective honouring the man and his 35+ year oeuvre that I felt now was the time in my life to jump headfirst into the Maddin madness. A screening of his debut feature Tales from the Gimli Hospital preceded by his landmark short film The Heart of the World followed by an audience Q&A with the man himself set the stage for our meetup the following day. We sat down at a nearby coffee shop where he discussed his career, influences, and how Hollywood managed to let him get away.

Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988)

For the uninitiated, can you tell us a bit about your background and what led you to become a filmmaker?

I was really lucky to chance into filmmaking. I’m 66 years-old now, but approaching my 30th birthday, I had no idea what to do with my life. Other boomers, my friends, had all become doctors and lawyers and I was still stuck in an undergrad state of affairs.

Since my mid-20s, I had wanted to make movies and I just got lucky. My first short film and first feature actually got into some festivals and critics started noticing me right away. It was fun, I liked to do it, I was proud and working hard. I hadn’t worked hard in my 20s and I felt very guilty about that. I was definitely the black sheep of the family and then all of a sudden they (the films) started to get a bit of notice in the newspaper and that was big currency in the family.

So I went all-in for filmmaking. It was definitely low-budget stuff. I found my niche in low budget-looking and feeling movies, experimental films and decided to develop and evolve as a creature in that realm. I really didn’t have any interest, nor any realistic hopes of becoming a slick, Hollywood-style filmmaker, so I didn’t even try.

You mentioned at the Q&A that David Lynch’s Eraserhead was a particular inspiration for you.

Right! David Lynch had a different background. He went to film school (and) he’s a great artist/painter. His soundtracks are very ambient, rich and murky. I heard an interview with him recently about how hard he and his sound designer Alan Splet worked on those things. Of course, I was just lifting sounds from old movies and things and laying them in. It was easy as pie for me.

He’s got all the fundamental filmmaking chops down. He went from Eraserhead to The Elephant Man which is an Academy Award-winning movie with real actors like Ann Bancroft and John Hurt. Whereas my follow-up picture to Gimli Hospital was just another one like that (1990’s Archangel).

Can you tell us a bit about your first films, The Dead Father (short) and Tales from the Gimli Hospital (feature) came about and what you learned in the process of making them?

I had no sense of visual style when I started making The Dead Father. But I knew I wanted to shoot in black and white because I didn’t know enough about how colour worked on a screen to control the palette with any confidence.

So I went with black and white. Not because it was cheaper, which it was, but because it would give me greater control over what was on the screen, namely black, white, and grey. That’s a palette that works!

I also didn’t know how to light with the basic three-light setup: key, fill and back-light. I thought I did! I studied up on it. Then when I went to shoot on the first day, my actors just had three noses shadows. The lights were bouncing all over the place!

So I unplugged two of the lights and just turned the actor’s faces to where they looked okay in relation to the shadows and where the camera was. I quickly learned that the middle of the frame was lit and then graded off to shadows. It created a lot of atmosphere. I reminded a lot of my early viewers of German expressionist silent films.

My films weren’t silent in the early days. My first silent film was in the year 2000 (The Heart of the World) with intertitle cards and everything. But people were always describing my movies as silent. They were mostly silent, but they had a silent movie aesthetic, a silent movie acting style, more uninhibited, things like that.

But these styles just evolved the way animals evolve over millions of years. You know, a duck-billed platypus needs to lay eggs even though it’s a mammal. I just sort of evolved into the Manitoba version of (a) duck-billed platypus: a guy who makes silent movies, but experimental autobiographical things with non-actors. So I just kept going with whatever enabled me to put the best thing on the screen.

Archangel (1990)

Your films are often said to evoke not only the silent era, but the early-talie era of the late 20s/early 30s as well. Can you talk about what draws you to that period?

Well, I was already assembling scripts that were like silent movie scripts. Silent movies are one big step towards fairy tales. I kind of understand narratives, books, and movies through the fairy tale door. I always enter into movies through the folk tale, the fairy tale, the broad strokes of those things. Once I’m inside them, then I’ll correct my take on a movie and try to understand what it is. But I always enter through that door.

When I was making my own movies, I tried to take psychological states that had obsessed me and present them in sort of fairytale fashion. So very quickly after I started making films and besides my movies started to look like German expressionist films because of the shadows and were mostly silent (I had voiceover narration), I became drawn to silent film and started watching more of it. I hadn’t particularly watched much of it before I started, but I noticed the similarity and thought I’d better go with this.

Then I learned about these part-talkies, films made in 1928 that weren’t released right away because they were (originally) silent and pictures were starting to talk and they realised that the public wouldn’t go see them. So they “goat-glanded” them (which is) where they would take them back into the studio and shoot a couple scenes with dialogue or put a musical number in.

I loved the idea of that. I loved the idea of having that option on your palette like a painter having the option to have dialogue that’s audible or dialogue that’s readable. I just thought “why can’t a director have both options?”. So I decided to do that and I liked it.

I heard once that something like 75% of American silent features are now lost forever with no copies available.

Yeah, it’s heartbreaking. One of my big projects was an internet-interactive (project) where I adapted many lost films into my own versions of them. To fund the internet interactive I had to turn some of them into a feature film assembly and that’s what The Forbidden Room is. It’s based on 17 lost film narratives that I researched and then shot in 2012/13.

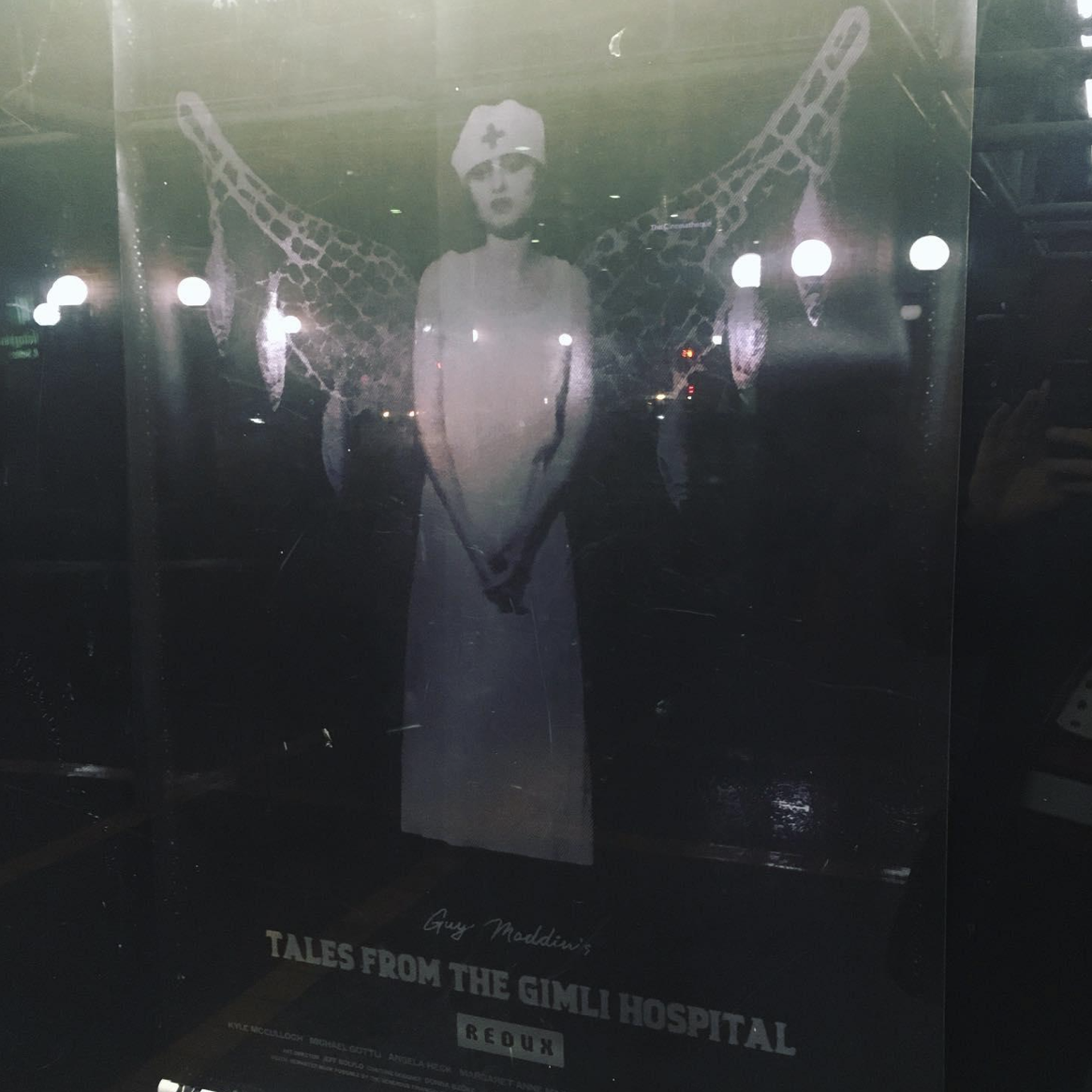

Gimli Hospital “Redux” poster

The version of Tales from the Gimli Hospital that was shown at the cinematheque was advertised as a “Redux” version. What was changed and why?

It was hard to resist. The colour-timing on it, how much contrast there is, was never done correctly on that movie. So I got a chance to show a little more (of the) set. The shadows could be just as dark, but the shadows could contain some information.

It’s not cheating, because that’s what I intended all along and it’s what the lab back in 1988 just didn’t give me. They were too lazy to tell me that they were printing on colour stock! They were too lazy to take colour stock out of the lab and put black and white stock in. That increased the contrast without nuance. So I always felt ripped off by the lab.

So when I heard I got the chance to do a 4K restoration, that was the first thing I thought of, to do a proper colour-timing of it. Once I re-visited it, I realised that I was really getting off on the sound of ambient crackle. It’s wall-to-wall in the movie, and I thought a long, slow fade to black full of ambient crackle was just a treat.

But by the time I revisited it last summer, I thought “Well, there’ll still be plenty there even if I cut (some) out.”. So every scene ended with a very long, slow, fade to black. Then some (more) black, then a long, slow, fade up from black and I cut those out. I literally cut minutes out of the movie just by cutting black and grey fade ups and fade outs out of the film and it just moves along a little faster now.

Then I added a kind of dream sequence. In 1999, eleven years after I finished making the movie, Michael Gottli who played Gunnar, got into a car accident (where) he hit a moose and he lost the ability to speak properly. He had a lot of memory loss and he couldn’t walk anymore.

He was really feeling down about this and we all felt bad for him. So I had a little reunion with some of the actors from the movie. We got together, I picked him up and brought him over to my apartment and we shot what I told him was just a “deleted scene” from Gimli Hospital. It was a really fun night with him, just one day. It was shot on the day John F. Kennedy Jr. died actually.

It’s that sequence that happens after the puppet show. There’s an anaesthetic scene that goes on and there’s fish slapping together, then a polysexual dream of some sort. Then it comes out of the dream. That was shot eleven years later just as kind of a therapeutic reunion of the team of actors and some new ones. It was really nice.

Then it just kind of sat as nothing until this fellow (Michael) passed away (from) cancer. He had the worst luck. So I thought as a tribute to him, I’d insert it into the movie. That’s the sum total of the changes.

Careful (1992)

Were you ever courted by Hollywood or the more mainstream Canadian film industry?

A very nice person named Claudia Lewis who was the vice president of Fox Searchlight in 1993 [sic] invited me down. She arranged some meetings for me with Madonna’s music video company and a couple other studios. It was a real whirlwind courtship. I had to take a taxi and pay cash to go all over LA (because) I didn’t have a credit card to rent a car!

But I was so green. I was just such an isolated Winnipegger who’d made these films with some friends and I didn’t know how to relate to these people. They were talking about actors and directors that I didn’t know who they were! I only knew dead actors and dead directors. So nothing much came of it and I just sorta gave up hope of ever going down there again.

But I’ve since started re-entertaining (it). I’ve made some friends in the business. So who knows? We’ll see.

I’m surprised a show here in Canada like Murdoch Mysteries hasn’t asked you to direct an episode yet.

I’d fuckin’ take it! I’ll betcha it pays well. I don’t think they’d have me. I’ve never been exactly welcomed by the establishment. Not that I’m a horrible person, it’s just that craftspeople tend to be unimpressed with the films (I make). Maybe even directors and actors who care about naturalistic performances aren’t impressed. Murdoch Mysteries wouldn’t want their weekly show to suddenly look and feel like one of my movies.

Hudson & Rex I’d do. I actually love Hudson & Rex!

Twilight of the Ice Nymphs (1997)

You mentioned at the Q&A last night that if you had grown up in a more film-industry oriented city like Toronto, you may not have become a filmmaker.

Probably not. I probably would’ve been a cineaste and you know, watched a lot of movies.

I remember the first film festival I went to, I quickly met the prominent members of the Toronto filmmaking community. Atom Egoyan was there, a guy named Jeremy Podeswa who is a top-flight TV director now, does Game of Thrones and stuff like that, and a few others. I just felt like such an outsider and just didn’t feel welcome in the community.

As it turns out, I’ve come to love these people now, but I just felt like such an outsider and didn’t feel like I could make films there. I didn’t know people there, but maybe if I’d grown up there….I dunno.

Especially New York. If I’d grown up in New York, I just woulda been checking out The Ramones and Patti Smith. I just woulda been a music scene-ster and overdose victim of some sort. But I was born in Winnipeg and I’m still alive.

To be continued!

Celluloid Dreamland: The Cinema of Guy Maddin is currently screening at the Pacific Cinematheque until February 20