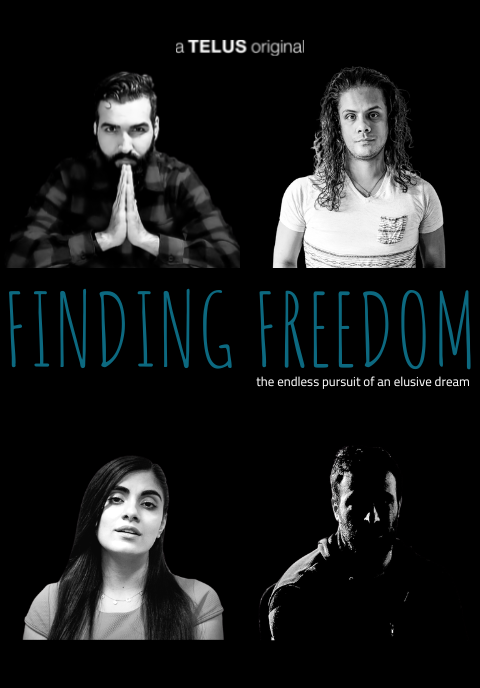

Writer/director Alan Goldman’s Canadian documentary “Finding Freedom” debuts March 3 on the Water Bearer streaming channel.

Finding Freedom follows four asylum seekers who after being detained indefinitely in an immigration detention centre, use their smuggled cell phones to document the deplorable, prison-like conditions and expose the daily violations to their human rights. In this thought-provoking and timely film, producer Mel D’Souza (SILO Entertainment) and director Alan Goldman shed light on the disturbing realities of certain refugee detention centres and show the challenges newcomers face even after securing freedom in Canada, among other countries.

“The ultimate aim of the documentary is to show that although the people featured in it are now free, their scars and wounds will haunt them for a lifetime”, says Alan Goldman, “As a filmmaker, I feel a responsibility to raise awareness of the human rights violations happening under the radar — to push audiences to question their beliefs and ask ‘is this how a civil society behaves’”.

On a pleasurable trip to Australia Alan heard about the human rights violations from the media which they mostly ignored “It just seemed so unbelievably barbaric. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. And I felt like I was very naive. I simply hadn’t thought this kind of thing was actually going on.”

The film depicts the camps as offshore prisons – part of Australian law to warehouse people who tried to make unsanctioned landfall by boat. As Alan dug deeper, he uncovered the widespread use of such detention camps.

In the film, Guardian foreign affairs correspondent Ben Doherty calls the current era the “age of displacement. ”In recent decades, more people have been forced to leave their homes than ever before in human history”, he says.

With help from organizations in Australia and abroad, Alan contacted four former detainees. Amir Taghinia, Ali Dorani and Negar Rezvani who were each provided a phone, and technical gear. The group recorded their lives as they began adjusting to Canada, the U.S. and Norway.

“I was really interested in personalizing their stories. I wanted them to have agency in how those stories were told,” Alan insists. He hopes the documentary will coerce ordinary people into feeling uncomfortable with the policies used by rich western countries to keep asylum-seekers from entering their country.

Amir, Ali and Amin each spent many years on Manus Island, a remote landmass off the coast of Papua New Guinea. Amin’s detention was nearly double that of the others, having spent 3,285 days in the camp. Negar spent 2,737 days in detention on Nauru, a tiny island nation where women, children and families were sent.

Each of the film’s subjects are currently trying to reestablish themselves in their adopted countries. Private sponsorship programs such as MOSAIC were vital to making that possible. But the effects of detainment psychologically can stay with one for their entire lives, Alan states. Amir, Ali, Negar and Amin each struggle with the impacts of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Canada has a migrant detainee population of roughly 9,000, including 100 infants and children, according to Efrat Arbel, associate professor at UBC’s Peter A. Allard School of Law. Ketty Nivyabandi, secretary general of Amnesty Canada, says no time limits exist for such detentions.

Until recently, detainees were often held in correctional facilities in British Columbia and across Canada. Both Amnesty and Human Rights Watch have campaigned successfully to change this policy. Quebec and Ontario, however, have yet to put an end to the practice.

“We should reexamine these policies and ask ourselves, is this okay? Are we okay with this?” Alan asks. “I’m not okay with it.”