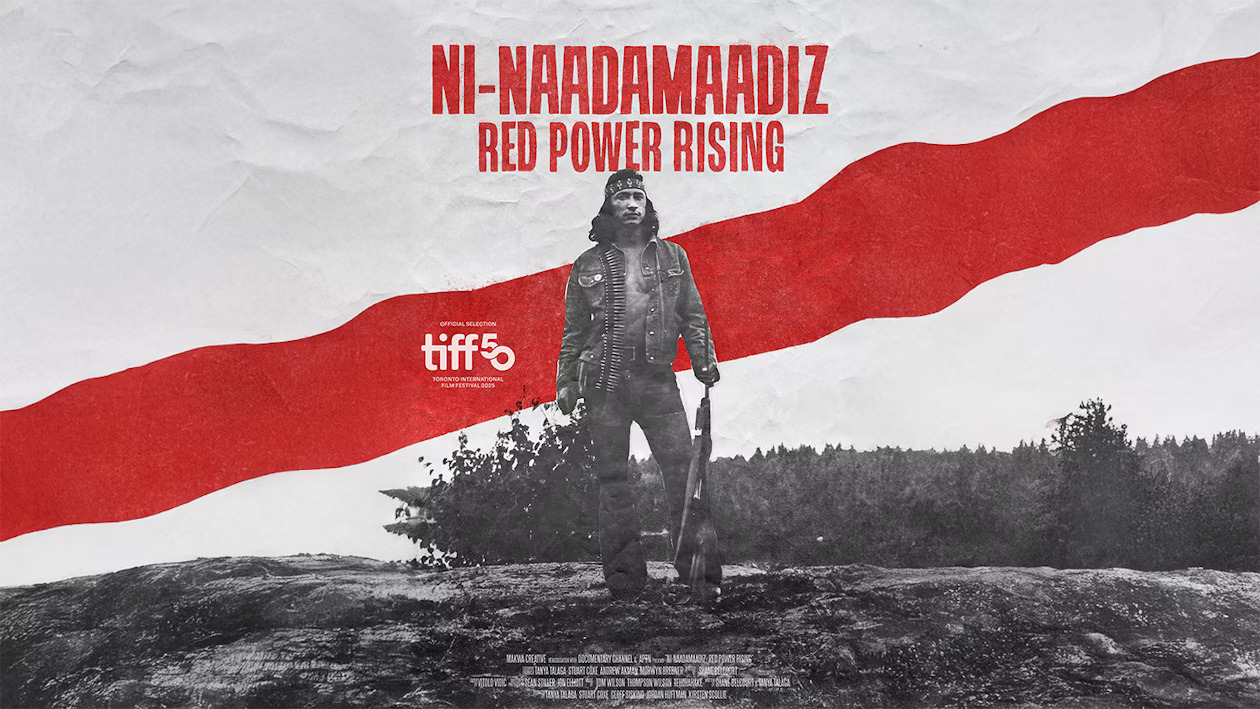

Some stories slip through the cracks of history, yet their echoes remain all around us. Ni-Naadamaadiz: Red Power Rising, premiering at TIFF 2025, brings one such moment back into focus.

Directed by Shane Belcourt and co-written with journalist Tanya Talaga, the film revisits the 1974 occupation of Anicinabe Park in Kenora, Ontario, a youth-led land reclamation that lasted 40 days and ignited a movement.

With only eight minutes of archival footage, Belcourt and Talaga work alongside community members to rebuild a story of resistance, spirit, and love for the land. Their film doesn’t just look back; it asks us to see how that call to action still resonates in today’s fight for Indigenous rights and the Land Back movement.

Revisiting a Forgotten History

In the summer of 1974, Anicinabe Park in Kenora, Ontario, became the stage for a pivotal yet largely overlooked act of resistance. For 40 days, roughly 150 Indigenous youth and community members occupied the park, reclaiming the space as their own and demanding an end to the relentless mistreatment of their people.

The late Louis Cameron and the Ojibway Warriors led the effort, drawing attention to issues that remain urgent today: illegal land sales, systemic neglect, and mercury contamination in local water supplies.

“This occupation,” director Shane Belcourt notes, “wasn’t just an act of violence. It really is an act of love, and it’s an act of love from the leadership to say, ‘I will step forward and put myself in harm’s way.’”

The Kenora occupation did not remain contained to the park. It sparked the Native Caravan, a movement that travelled all the way to Parliament Hill in Ottawa. What began as a peaceful demonstration ended in violence when police descended upon the group, a stark reminder of the state’s willingness to suppress Indigenous resistance.

“When you tell the story of Louis Cameron or the occupation of Anicinabe Park in 1974, what you’re really telling is a story of Indigenous self-love and Indigenous perseverance,” says Belcourt.

His words underline what many at the time already knew: the fight for justice was never just about confrontation, but about survival, dignity, and the determination to build a future rooted in community and spirit.

A Story Pieced Together

Telling the story of Anicinabe Park wasn’t easy. Despite the occupation lasting over a month, only eight minutes of archival footage exist. That’s all history left behind in official records. For filmmaker Shane Belcourt, the scarcity was both a challenge and an opportunity.

Initially imagining the film as an archive-driven work in the vein of MLK/FBI or Attica, Belcourt had to pivot: Despite having very little archival material, the filmmakers pooled every available resource to create a film that serves both as an essential historical record and a compelling commentary on present-day issues.

Co-writer and producer Tanya Talaga dove deep into research to fill in the gaps. She combed through newspapers, radio broadcasts, magazines, and personal archives. “We went far and wide… And of course, as is always the case, the people that helped us most are in the community and actually in Kenora itself,” she recalls. Some of the most valuable sources, news clippings and photos were privately held, saved by individuals when public records vanished.

The film also finds its emotional core in personal testimonies. Tyler Cameron, son of Louis Cameron, gives voice to his father’s unpublished memoirs, reading passages in Ojibway. Belcourt describes these moments as vital in carrying the story forward: “While we were taping those [sessions], she [voice coach Jules Koostachin] would just ask questions like, ‘What do you think about what you just read?’ We wound up using the off-the-cuff conversations with Jules.”

These interwoven perspectives transform the absence of archives into a chorus of living memory, reconstructing history not just through documents, but through the people who lived it.

Belcourt’s Vision: Call to Arms, Call to Spirit

For director Shane Belcourt, Ni-Naadamaadiz: Red Power Rising is more than a historical documentary. It’s a meditation on what it means to resist with love. “You could say it’s a call to arms,” Belcourt explains. “I’ve always thought of it as a call to spirit.”

Belcourt connects this idea of spirit directly to his own life. His father, Tony Belcourt, has been a leading figure in the fight for Métis and off-reserve Indigenous rights since the early 1970s. “That is something I knew very well from seeing it firsthand,” Shane reflects. For him, telling the story of the Ojibway Warriors is not just an act of filmmaking but also a continuation of the work his own family has long carried.

Through this lens, Belcourt reframes resistance as an expression of love. It’s the willingness of leaders like Louis Cameron to put themselves in harm’s way so future generations might inherit something better.

His words linger: “When you tell the story of Louis Cameron or the occupation of Anicinabe Park in 1974, what you’re really telling is a story of Indigenous self-love and Indigenous perseverance.”

Tanya Talaga’s Contribution

Journalist and author Tanya Talaga brings both rigour and heart to Ni-Naadamaadiz: Red Power Rising. Her path to the story began while researching her book All My Relations and later through her Audible podcast Seven Truths. The deeper she dug into the 1974 occupation, the clearer it became that this overlooked history needed a documentary treatment.

But with only eight minutes of archival footage, the task was daunting. “We went far and wide,” Talaga says of the years-long research process. “We were looking through newspapers, old footage, radio footage, magazines, journals, everything possible… The newspaper articles, for example, are privately held because they’re no longer in the Kenora public library. Those news clippings are somehow all gone from the time of the occupation. They were privately sourced from someone in Kenora, and that was huge.”

What proved especially powerful for Talaga was finding photographs of the young Ojibway Warriors who led the stand. “They were so young,” she recalls. “A lot of my work is around Indian residential schools and particularly the situation of our rights in northern Ontario, so seeing this come to life through the words of Louis and his manuscript, through getting to know Lynn [Skead] and Louis’s sons… it was just wild seeing it and knowing that nothing really has changed in Kenora.”

Her reflections tie the film to the present. The same communities that occupied Anicinabe Park are still in court, fighting to reclaim the land nearly 50 years later. And the injustices continue, she points to the police killing of Bruce Wallace Frogg in Anicinabe Park, and the unresolved death of teenager Delaine Copenace nearby. For Talaga, the film isn’t just history; it’s an urgent reminder that the struggle persists.

Contemporary Echoes of Anicinabe Park

The story of Anicinabe Park resonates far beyond 1974. Many of the issues that sparked the occupation, land rights, water contamination, and systemic neglect, remain painfully relevant today.

Talaga emphasizes this ongoing struggle: “The three communities that are situated where Anicinabe Park is are presently in court fighting the government of Canada to get that land back 50 years later… We’re in court now trying to get that land back for our First Nations. That is the number one thing that speaks so clearly to me.”

Belcourt and Talaga’s storytelling bridges past and present, framing the occupation as a precursor to the modern Land Back movement. Through these narratives, viewers are invited to recognize both the historical struggle and its contemporary significance, understanding that Indigenous perseverance continues to shape Canada today.

The Collective Spirit of Ni-Naadamaadiz

With so few archival records, Ni-Naadamaadiz relies on the voices of those who lived the events to reconstruct history. The film becomes a chorus of perspectives, blending testimonies from Louis Cameron’s family, the Ojibway Warriors, and community members like Winona Wheeler, who recalls small acts that kept the occupation alive, like peeling potatoes or carrying coffee under gunfire, laughing even in the face of danger.

Belcourt notes the importance of authenticity: “There’s something about the authenticity of people from a place: the way they speak, the temperament, the tempo, those things that have a je ne c’est quoi about how you’re framing and hearing the story.”

Music by Tom and Thompson Wilson, under the name Tehohàhake, further amplifies the communal spirit, linking past and present. By highlighting the collaboration of community, family, and artists, the film shows that the Red Power movement was sustained not by individual heroism alone, but by collective dedication, humour, and resilience.

About Shane Belcourt

Shane Anthony Belcourt, born in Ottawa, Ontario, in 1972, has long focused on telling stories that celebrate and explore Indigenous identity, culture, and resilience. The son of Métis rights leader Tony Belcourt, Shane grew up immersed in the fight for Indigenous rights, a perspective that informs much of his work.

Belcourt’s career spans both narrative and documentary filmmaking. He gained recognition with his debut feature Tkaronto (2007), which explored the lives of urban Métis and First Nations people, and has since directed films including Red Rover (2018) and Warrior Strong (2023). His documentary Beautiful Scars (2022) examined musician Tom Wilson’s late-life discovery of his Mohawk heritage.

With Ni-Naadamaadiz: Red Power Rising, Belcourt continues his commitment to spotlighting Indigenous stories, blending history, personal narrative, and communal memory to create films that educate, inspire, and provoke dialogue.

Wrapping Up

Ni-Naadamaadiz: Red Power Rising shines a light on a crucial, yet often overlooked, chapter in Canadian history. Through the eyes of Shane Belcourt, Tanya Talaga, and the community whose stories they bring to life, the film captures the courage and resilience that sustained the 1974 Anicinabe Park occupation. It reminds us that Indigenous resistance has always been grounded in love for land, family, and community, and that these struggles continue today in the Land Back movement.

By blending archival material, oral histories, and intimate perspectives, the documentary invites viewers not just to witness history but to reflect on the ongoing fight for justice, equity, and recognition.

(Quotes featured in this post are from povmagazine.com.)