Cinematic exercises in surrealism are never simple, whether it be in their execution or consumption. However, it’s the essence of this challenging nature that can make their thematic delivery more profoundly impactful than a work operating within the means of realism. David Lynch has based much of his career around such an ethos, while the works of Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel are considered seminal in bridging the gap between absurdist literature and the moving image.

Nobel laureate Octavio Paz, whose own literature falls within the realm of surrealism and existentialism, even recognised the singular brilliance of Buñuel’s work, calling it “the marriage of the film image to the poetic image, creating a new reality.” Paz’s words characterise surrealist cinema in a manner few ever could, while conveying his own unique perception of the genre regardless of its medium.

Iranian filmmaker Amin Sameti, in his short film Blue Eyed, attempts to combine the literary sensibility of Paz’s works (particularly “The Blue Bouquet,” upon which the 7-and-a-half-minute film is based) with a more subdued approach to Buñuel’s subversive imagery.

Sameti cleverly emphasises the importance of sight and sound in the very opening image of Blue Eyed, where the two senses are overloaded by white noise emanating from a television in a grimy apartment. Moments after the opening, this sensory barrage gives way to a talk show called “Tonight,” where its obnoxious host interviews, or rather mocks, an up-and-coming actress intriguingly named Mrs. Random, whose blue eyes are recognised as the key to her success, given that “blue eyes have become very important these days.” Sameti does a lot here, establishing several themes in just over a minute, as well as some well-placed world-building. Upon first viewing this can all seem a little obtuse, though repeated viewing is a mandatory hallmark of any surrealist work that is to be considered truly accomplished. So far, so good.

As the interview continues, the unnamed lead character wakes from his slumber in front of the television and chooses to leave his stifling apartment for some fresh air. Just as he is about to leave the building, its apparent owner questions his decision with an air of omniscience that is very much at home in almost any work of surrealist fiction. Up to this point Sameti has shown adept control over his short’s tone, which complements his frequently enigmatic writing.

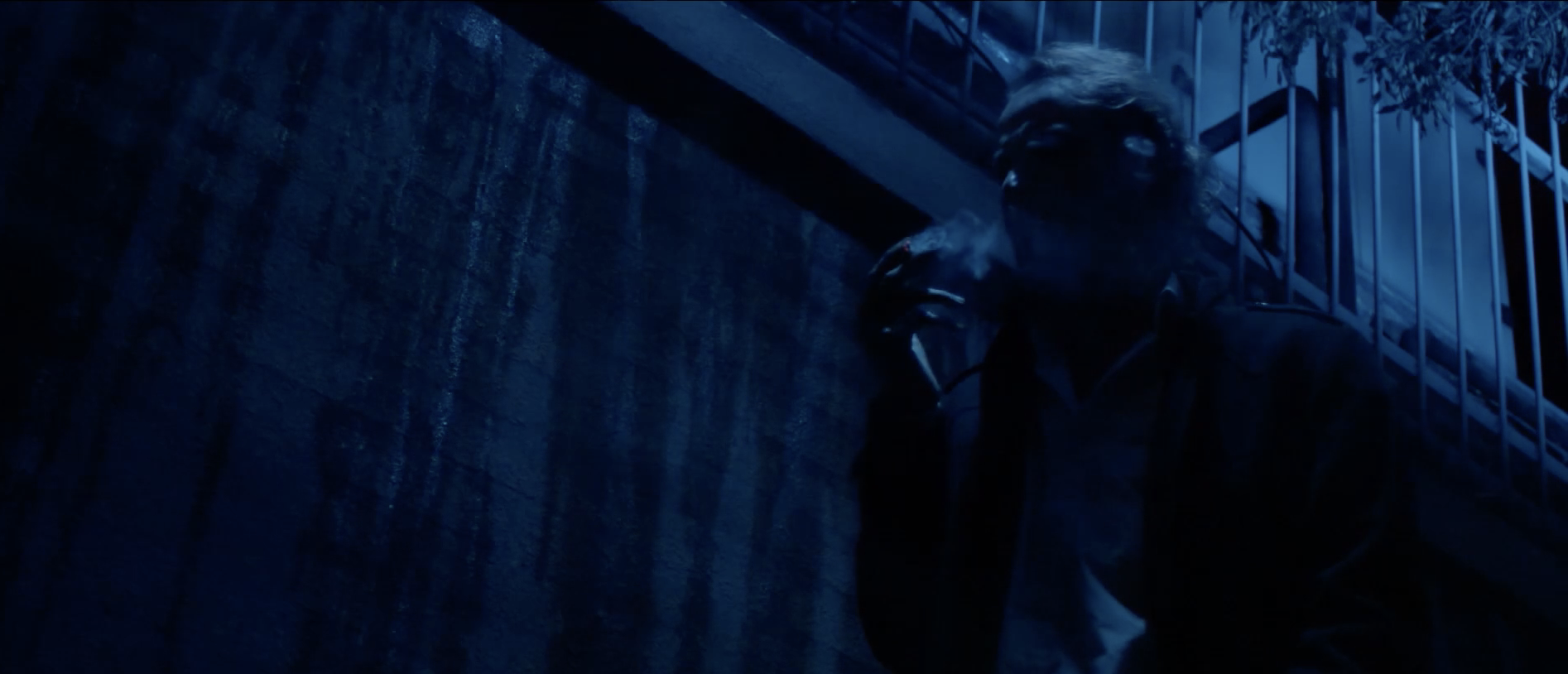

After leaving the building, a brief scene ensues where the lead finishes his cigarette, which Sameti depicts with a flourish that emphasises the importance of sight and sound, though its edge is somewhat dulled by cliched sound editing. Sparing lighting effectively sets the tone for what’s to come next, as the lead is held at knife point by a masked mugger, and it’s here that the short momentarily buckles under the weight of its own accumulating intrigue.

In their exchange, it is revealed that the mugger is not seeking money, but rather blue eyes, which he believes the lead possesses. Surrealist works need not rely on dialogue necessarily, but in this particular scenario there is a wealth of potential for a meaningful back-and-forth that could be used to further Sameti’s well-laid themes up to this point, but instead the mugger simply tells the lead he needs blue eyes for his wife, checks his eyes, which are brown, and then leaves him be. Minus a few other inconsequential details, that’s the whole scene. For such a moment, which is at the very centre of Sameti’s short and clearly crucial, its bafflingly reserved execution is severely wanting.

Blue Eyed does manage to get back on track with some of its concluding moments, as the lead makes his way back to his apartment building, passing two individuals along the way who are missing their eyes. This brief encounter adds some badly needed depth to the disappointing encounter with the mugger, though nowhere near enough to compensate for its significant shortcomings. I am unsure yet of its true meaning, but the very fact that I was intellectually stirred by it does great service to the short’s surrealist sensibility, given that this has always been the purpose at the very heart of the genre.

Although I have already discussed the beat-by-beat story of Blue Eyed to this point, I will stop short of revealing the final scene in order to maintain its most hard-hitting moment, which does admittedly grant a little more context to the mugging scene, but suffice to say my impressions of the short are mixed. Its themes are, for the most part, well realised and cryptically stimulating, while each viewing reveals wrinkles that add further nuance to its visuals and narrative. However, surrealist cinema lives and dies by the execution of its absurdist elements to tell a richly layered, cerebral story, and Amin Sameti’s lack of conviction in what should be the short’s most crucial scene undermines not just his core intentions, but the spirit of the very genre itself.

5/10

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()