I’ve never experienced a commingling of reality and fiction quite like Ryan. As a matter of fact, I don’t think I’ve ever experienced anything quite like Ryan. The closest comparison I can make is with David Cronenberg’s wonderfully subversive Camera, yet this does little to articulate Ryan’s true essence, as well as its lasting impression on the animated short film.

Ryan, at its most basic level, is an animated documentary film. What’s immediately intriguing is that it is based around an interview conducted by Toronto-based American animated filmmaker Chris Landreth with his friend, the titular Ryan Larkin. For those who may not know, Larkin was a groundbreaking animator from Montreal whose most famous works, Walking (1968) and Street Musique (1972), not only made indelible marks in the history of animation, but also earned him two Academy Awards nominations in the Best Animated Short category. Thus, it’s fair to say that Larkin’s own work influenced the very animator who was now making a short film about him.

However, a life of neglect and tragedy, in addition to being abused by the very industry in which he worked, led to a life of drug addiction and alcoholism, which the documentary discusses in a brief but informative manner.

Ryan went on to become one of the most celebrated animated shorts of the 21st century, drawing significant acclaim for its originality and depth. The film won dozens of prestigious awards in the short film category, including an Academy Award, the very prize that eluded Larkin himself.

What truly sets Ryan apart from the competition, though, is the way in which the animation and real-life subject matter coalesce to deliver a transcendental short unlike any I have ever seen. Admittedly, by today’s standards Ryan can initially come off as somewhat low-budget and indie. At certain moments, there is an almost deliberate unfinished sensibility to it. Even I took a few moments to appreciate what its beautiful and occasionally messy animation style was trying to achieve, but soon enough it clicked, and I had one of those rare epiphanic ‘Aha!’ moments that evoked my most fundamental love of cinema. Ryan is a fine wine that grants a newfound appreciation for its bottle’s aesthetic after a single taste.

All this begs the question: why bother animating the interview in the first place? This leads me to what is undoubtedly Landreth’s greatest stroke of genius, as his use abstract computer-generated animation expresses truths that would struggle with conveyance in a live-action setting.

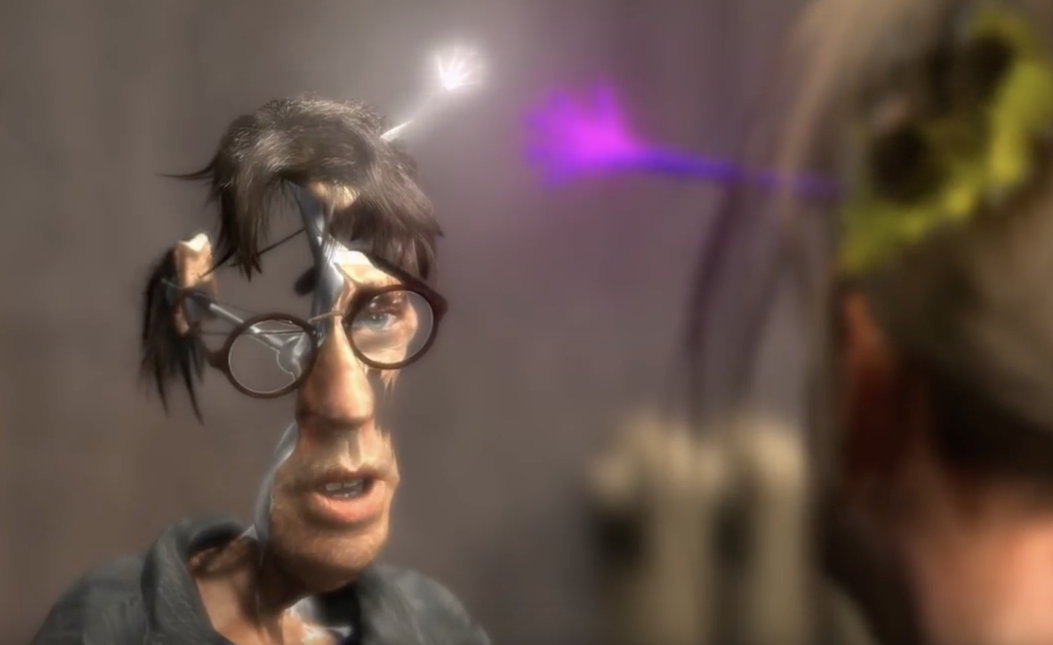

The vast majority of events in the film are in fact happening, but it is through Landreth’s own mental perception of the world and those who populate it. As such, the grimy cafeteria in which Landreth interviews Larkin features the likes of a grouch who’s hairy enough to play Cousin It in The Addams Family, a man with a grossly exaggerated head, and a slouch who has half melted into his table and chair but still continues to smoke his cigarette. The animation here is creative and whimsical, but then there’s the distinctively similar depictions of Landreth and Larkin.

When looking in the cafeteria’s bathroom mirror of the opening, which initially takes place in the film’s version of reality, Landreth explains that the various chunks missing from his face were stripped away by the harshness of life, one of which was when his “unbridled romantic world view was permanently shattered.” Despite the significance of such a negative life-changing experience for Landreth, his visage is still largely intact. The same, however, cannot be said of Larkin.

By giving us context prior to Larkin’s introduction, we are left in shock at the sight of a man so psycho-physically threadbare that the lifelong hardships of the gifted animator are painfully clear. He is the embodiment of his own tragedy. Such a characterisation would not be possible without the use of animation and, given the film’s short length, can only inherently convey so much information on Larkin’s life. Such a striking technique evokes a visceral response that even 14 minutes of straight dialogue couldn’t hope to achieve.

I could go on about the depth of Landreth’s work here, but there is frankly enough to unpack in Ryan’s brief runtime for an entire book on its subject matter and abstract depiction of trauma. Ryan intrinsically remains as impactful today as it was upon release in 2004, while paying homage to an influential but tragic figure of Canadian animation.

Larkin sadly died in 2007, though the short film’s success gave him a fresh lease on life as well as new opportunities in animation during his final years. While one can only lament the time lost during his most turbulent years of addiction and having to panhandle to make a living, it is comforting to know that Ryan Larkin’s memory lives on not only in his own significant works, but also one of the most accomplished animated short films of this century.

I have intentionally avoided giving away too much about Ryan, so if you would like to view it, it’s available to stream on the National Film Board of Canada’s official website, or their channel on YouTube. Links for both will be included below.

NFB Website: https://www.nfb.ca/film/ryan/

NFB YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbkBjZKBLHQ