If we all took the time to walk in each others shoes perhaps we’d be less quick to judge, perhaps we’d be more quick to care and perhaps the world would be a better place.

One thing that fascinates me are people and the psychology behind what makes us so different. I believe that for the most part, what you experience in life is what shapes you. Some of the most positive people I have met have had a history of sorrow and bad luck and yet they are able to find the silver lining through all the dust and debris. How do they do it? When we are children we are free from judgment, we don’t envy, we don’t worry about everyone else’s business and we are always looking for a new friend out of companionship. When we grow older, we forget our innocence and many will build an invisible wall around themselves that will only open when they decide. I think we should all get back in touch with our inner child; it’s a much happier life.

Now imagine that you have a disability, either from birth or from an accident or disease and are confined to a wheelchair. The cards are stacked against you and a smile or kind hello may be the last thing people would expect out of you, but yet you soldier on like it comes easy. I certainly don’t subscribe to painting every minority with the same brush and we’re all entitled to react to a bad day. While children have no inhibitions of approaching a disabled person to say hello or ask a question as to why they use a wheelchair, many adults prefer to play it safe and walk past like they didn’t see them. How do I know, because I’ve had the luxury of knowing both sides of the coin. I became wheelchair bound after a car accident when I was 28 years old. I’ve learned so much about social acceptance and perseverance but being able to love yourself and becoming the best version of myself is what counts the most. When life throws you broken glass, use it to reflect but keep moving forward into the storm. There is sweet sunshine waiting on the other side. Life doesn’t end it just changes the rules. Somebody born with a disability that is wheelchair bound from their first moments in life has never known another life and yet they to can often be seen sporting a smile; case and point, Andrew Gurza.

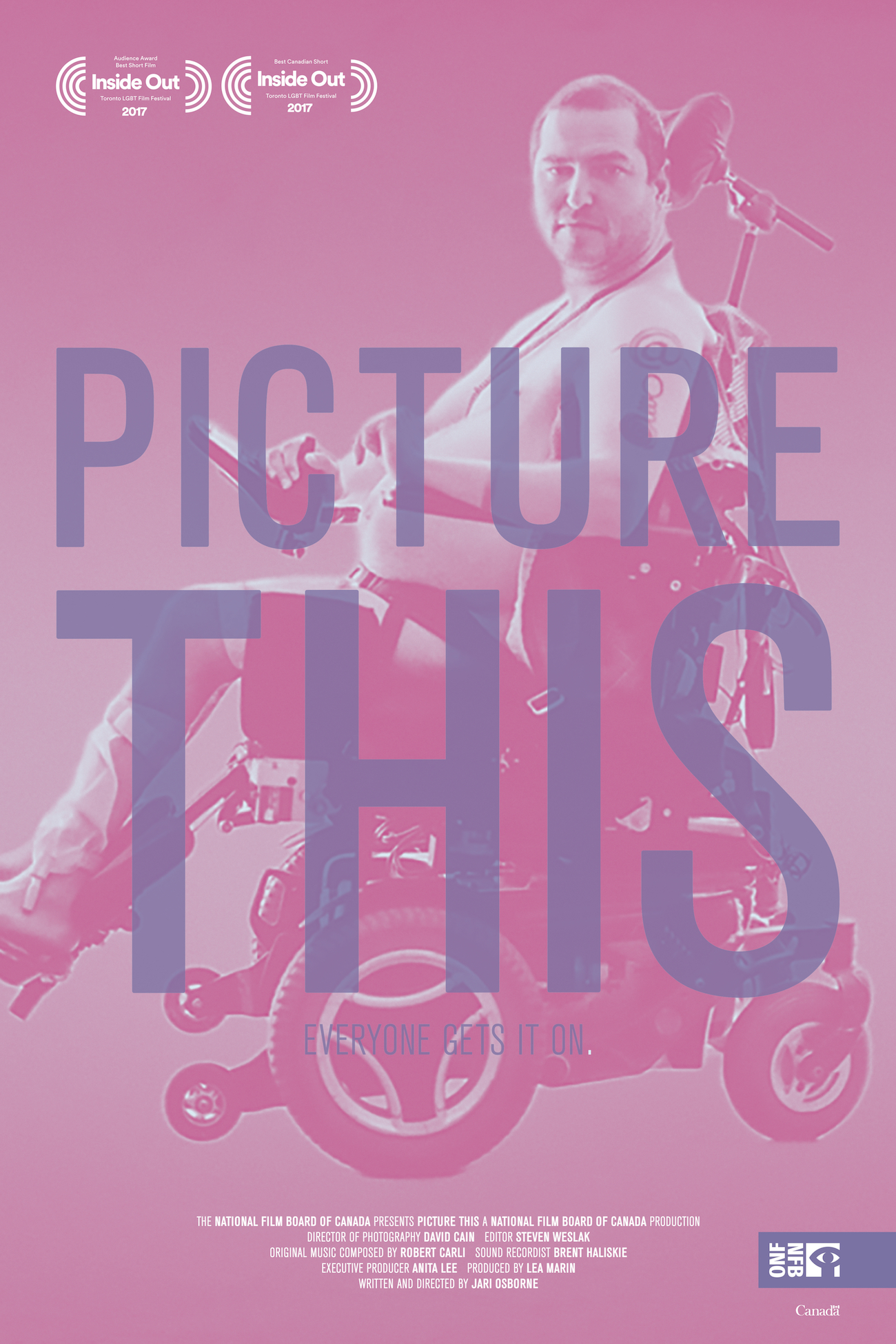

Andrew was born with a disability but his attitude and charm are a cut above the rest. Award winning documentary filmmaker Jari Osborne had recognized Andrew’s amazing tenacity and veracity for change around how society views the disabled… especially when it comes to sexual relations. The film is eye opening and sometimes jaw dropping but it is also educational, very inspiring and deserves to be seen. Picture This is the result of Jari’s cunning intuition for incredibly captivating stories that help understand the human condition inside and out. We caught up to her while enjoying a coffee in Vancouver.

“What was the process like, trying to get enough interest in this film?”

“When I had the idea for the film I had pitched it to a broadcaster, which will remain unknown. They weren’t supportive of it but the National Film Board was. They wanted me to do more research because the subject is about sex and disability and wanted to be sure that I could find genuine people to discuss it openly with while being vulnerable. Once I had some footage to bring back that I felt was very strong, I showed it to the NFB and the broadcaster (who had previously screened much of my stuff). The meeting with the broadcaster didn’t go as expected and they lost interest. I had to go back to the NFB and tell them that we didn’t have a partner. We had decided to go ahead with the making of the film anyways. I’m really proud of it and glad I completed it.”

“I felt that I had learned much from this film. Talking about sex and disability is very important in removing the stigma. In the documentary there is a scene in which a disability orgy had been organized. At first the idea seemed shocking and novel but at the same time it had to be very liberating for the participants. What is your take on it?”

“One of the things Andrew wanted to do was to have the discussion of making sex more accessible for people that don’t have the same access for many different reasons. There’s the social bias as well as the physical inabilities of having sex like able-bodied people. For me it was interesting to do the story also interesting to find my own connection to the story. I’m not gay and don’t have a physical disability so it was a bit of a challenge for me to find what my connection to the story was. I really had to go back to the first piece that I ever did. My documentaries have a common theme about people on the outside that don’t feel they belong but want to find a way in. My first documentary was about my father. As a Chinese/Canadian, he was denied all kinds of basic rights even though he was born here. He was denied the right to vote, denied the right to work in certain places and was really marginalized. I didn’t find out that he’d volunteered for the army and was in special-forces with a commando unit behind enemy lines until I’d made the documentary. My dad would tell me that every morning he’d get up he’d feel like an animal instead of a human being because he didn’t have his basic right or sit in certain areas, such as a movie theatre or other places. I realized later that what Andrew was talking about and expressing was the same thing as my father. He’d tell me that having gone through all these experiences with his sexual identity, he was either mocked, ignored or denied which made him feel less than human. When I look back at the piece I feel like a lot of things have changed but his generation and all the things they did have paved the way for us and the next generation.”

“The comparison does certainly have its similarities even though they’ve lived very different lives. Can you explain the similarities?”

“My father joined at the age of 18 and was flown to India for commando training and taught to jump out of planes. He was then dropped behind enemy lines and had to fit in amongst the population without any promises. The struggle to be equal is so precious and yet so painful and joyful at the same time. I guess I’ve always understood that we tend to value some people over others, historically and culturally. I thought that ended with my father but when I talked to Andrew and learned what the movement was about, to claim your sexual identity it felt like a familiar story. I didn’t set out to make a film about sexuality or disability, I was so compelled by Andrews commitment, his work and his wonderful personality. I thought I was telling a story that mattered to him.”

“How did you find Andrew?”

“I had known a little about what he did but I wasn’t really driven to the story until I saw a photo in the paper of a young couple; a beautiful young woman in a wedding dress leaning over her husband who’s in a wheelchair. It was a very arresting photograph with a write up. After reading it I realized they were a couple from my neighbourhood. I suppose I was a little surprised at their relationship, which I had to process like many people. You don’t understand and we have these biases. Many people would find it surprising but I don’t anymore. Andrew was a friend of theirs and they wanted me to speak to him. I’d already previously heard some of his podcasts and read some of his writings. I knew it was an interesting story and it fit into the same theme as my other pieces. Who would’ve thought?”

“What happened to the young couple?”

“I think in the end they really wanted to do the piece but I believe there was a lack of trust in moving forward with telling their story accurately. With Andrew, he was very honest and started telling me about his lived experience. With the other couple, we never really reached that level and I believe they really wanted to control the narrative. I can’t work that way. My pieces are about what I see and you can only approximate the truth and capture the gravity to create what you know and understand it to be. You put it out into the world and wait to see if anyone else feels the same way.”

“How long did you follow Andrew?”

“For about 1 ½ years. I had met him in Toronto just before he threw the first party, which was a huge success. We didn’t get that one on tape because we didn’t know each other that well. With the second party, Andrew had hoped it would attract more people and that it would be more significant than the previous year. Unfortunately, the novelty of someone throwing an accessible sex party was over. The Howard Sterns of the world had already had him on because this was so interesting and so sensational, so taboo and so unbelievable. The talk of hydraulic lifts to allow people to have sex, assistants to help with positioning and all of that. Were they going to allow people to masturbate or were they not and if they couldn’t, were they going to help them? There was all these questions and it was such a sensational topic. I think Andrew was prepared to open the door and in his own dignified, witty and funny way he’d take on those interviewers. Some of the stuff he had to put up with was very undignified. When the second party had been booked, I thought it would be a great way to wrap it up because we had captured so much information and footage but then the party got cancelled. There was no interest from media or support from the community. They were basically ignored. It was almost exactly a year from the previous party.”

“Was it a matter of not advertising the event enough?”

“Andrew had said that they endured being dubbed the big disabled orgy last year and knew that when it happened they were taken back and realized it had elevated them to the top of a publicity list.”

“Is any publicity considered good publicity?”

“He’s had both. He’s felt completely invisible to people and he’s also felt like a freak show. In terms of meeting people he says it adds a layer of anxiety. If he’s searching on Tinder he doesn’t know if he should mention the chair or try to win them over with his charm and personality. He’s had people disappear into an elevator and not come back out. At the heart of it, it’s pretty devastating.”

Jari adds,

“He doesn’t let anyone tell him that his life should be lonely and untouched. There’s a lot of strength and beauty in that. He’d talk about high school and how he’d be excused from the class every time they had a sex-ed talk. The teacher would just assume it wouldn’t be relevant to him, nor did they think he’d want to think about it.”

“Was your approach quite different from the others you’ve made?”

“The piece is slightly inevitable in terms of the way it wears out but it wasn’t easy to find a structure for it. I spoke with my editor, who I’ve worked on a lot of pieces with. We talked about it for a long time and tried to put it together in different ways. It didn’t seem to work and we didn’t quite know why so we ended up doing it chronologically. It was like, this is me; meet Andrew. He has a really devastating birth story that we don’t use in the film. There are so many rich moments that bubble up as you continue to harness your material. This is also the first piece I’ve done without any narration. I wanted it more organic and for people to speak for themselves and be themselves. I’m really used to writing and continuity but for this one there’s no narration at all. It was a real humbling experience for me to make the film in a couple ways. As a filmmaker I was trying to rethink my whole approach to capturing reality/things on film. After doing many films you tend to get used to relying on the usual tropes of storytelling. As I’m in it I’m setting it up in my mind, thinking about how I’m going to shoot this thing and what I’ll need to cover it and what I’ll need to cut it and correct it.”

“Was there ever a discussion regarding the limitations of what could be filmed?”

“We did have a discussion early on about everything we’d be shooting beforehand. It was really important to me to find ways to honour the subject matter and respect his experience. I realized the camera would have to be at waste height and at an angle. We’d need a steady-cam of sorts to help support and cradle the camera. We talked about the shower scene, we talked about nudity and other things. At any point of filming if he felt uncomfortable we would talk about it. I would sometimes tell him why I needed to shoot a certain piece and in return he’d tell me what he would need to feel comfortable. He was really willing to put himself out there and be completely vulnerable. I do believe he trusted me and he trusted the process.”

“How small of a crew did you use and did you have to keep rotating the crew out, considering you were filming over the span of a year?”

“Most of the time, if we were filming in his apartment it would only be me, the cameraman, sound man and maybe a PA. When we were out with him covering his talks and things, we had a fairly full crew. We tried to use the same people. I think it’s extremely important in a documentary like this where you’re talking about sex and disability. When you put the two together, it’s not easy to process.”

Jari continues,

“My brother-inlaw really loves the film. There was a lot of apprehension out there surrounding the idea of the film and many people didn’t want to get on board. Lea Marin (producer) and I had to hoist it onto our shoulders to get it made and get it out there. We were really happy when it started making the rounds of the film festivals. It not only won a number of jury awards but it also won a number of audience favourite awards too. Winning on both sides feels great.”

“What was your expectation for the audience upon viewing it?”

“I never doubted that the film and Andrew were both compelling. Andrew’s ability to be the heart of the story is quite remarkable. He’s like a Trojan horse about the whole thing. He’s very comfortable with himself and his body, as well as people seeing him naked. He did a Boudreaux photo shoot and was naked. It was so amazing and really beautiful. I don’t think a lot of people could do that in his position because I think a lot of people are afraid of rejection. He prefers to put it out there and have people treat him like a freak show rather than, he doesn’t exist.”

“I think you made an amazing film that represents Andrew and others with disabilities. When you see him, you see the human being in that chair as opposed to just an object in a chair.”

“It is very apparent and it’s also why this film was so important for me to make. It changed me. It really changed me as a filmmaker. Sometimes you feel like you can compress certain sequences but on this film I never had those same devices or techniques available to me. There were times when Andrew would be too tired to continue and we’d shut it down and that would be it. Therefore some of the sequences and takes ran a bit longer, there were fewer cuts and less manipulation, although there is still a lot in the editorializing I did with the graphics and other touches.”

“What is the biggest message in this film?”

“It’s hard for me to answer that question because I don’t see myself as an activist or political filmmaker. I’m a storyteller compelled by the stories that I find and want to share with people, so I don’t have a prescription for a takeaway. I try to find something that’s feels amazing, significant and necessary to share. I then try to put my pieces together so that it communicates that. Then I put it out there. When someone comes back and says that’s amazing I feel the same way, it makes my world feel bigger and much more connected. I really hope everyone will fall in love with Andrew the same way I and everybody else did that had worked on the film. Andrew is very physically disabled and I don’t want people to look away, I want them to look directly at him and see him. I want people to connect with him. I think that’s what I’ve done with most of my films. I try to show how someone is considered not quite human enough and why is that so. They then show us why they are by opening themselves up.”

Jari Osborne makes the types of films that most would hesitate to start. She tackles tough subjects that open a window into a life we might otherwise notice. The subject of sex and disability are very necessary. Society needs to face their fears and explore more minorities to be able to remove the stigma. We can all benefit from it.

Picture This is free to stream on nfb.ca

Picture This, Jari Osborne, provided by the National Film Board of Canada