There are places that you might travel to that truly take your breath away. These are the kinds of places we only get to see in pictures or magazines. We long to visit but then life sometimes gets in the way and you resort back to the photos and magazines. What’s ironic about these destinations; you want to go because it’s missing in your life. They have a way of rebooting your thought process and will emotionally bring you back to the starting line. Everything is new again and awaiting exploration. Theses places don’t have speed limits because the pace is set by you. Take your time and drink it all in. Take big gulps or small sips. Getting inspired one step at a time while On The Edge Of The World is what Haida Gwaii can do for you.

I had the distinct pleasure of speaking with Charles Wilkinson, the creator of this visually stunning Haida Gwaii documentary. It was extremely informative, captivating and inspiring. Incidentally, the Archipelago is also known as the Queen Charlotte Islands. The area is a magnet for artists that have either migrated there or have grown up in its majestic surroundings. The Pacific islands are surrounded by warm currents and the weather is pretty moderate. Charles lives in Deep Cove in North Vancouver but travels there at least once a year.

“What was your personal interest in making this documentary?”

“I’ve been associated with Haida Gwaii for most of my life. When I was first getting started in the business I worked on a number of films about Haida Gwaii as a sound person or music composer so I had a real familiarity with the place. About 8 years ago one of our earlier films were invited up for the Haida Gwaii film festival. When we went, we met so many people there and heard their stories. We realized that a remarkable story exists on that Archipelago.”

“What time of year did you shoot the documentary?”

“We shot it throughout the year. In the summer people were calling it Hawaii Gwaii because the weather was so nice. We were also there in the winter and fall. It can get grey at times around the herring season.”

“I felt like I learned much from watching this film, especially in regards to the herring spawning season. I didn’t realize their eggs caused a milky colour in the water only visible from above. It was a great use of the drone.”

“We actually created a drink while we were there. It’s our contribution to Haida Gwaii culture. You take the gow (that’s the herring roe that attaches itself to kelp) when it’s on a kelp leaf and stick it in a martini glass and fill with vodka. It’s kind of like caviar; it’s a little salty and crunchy. It’s delicious and a bit of a delicacy. If someone knows there’s a herring spawning going on they’ll take some back and give it to their friends. The herring eggs kind of pop in your mouth and look a lot like tapioca and they’re just so delicious.”

“I noticed that there was a lot of archived footage of early logging in your film. Was it difficult to find the footage?”

“Not at all. CBC covered that and they’ve been very good at archiving and giving us access to the footage. It’s not inexpensive but it’s not prohibitive. They’ve got a big library but it is time consuming going through it.”

“How much of a team did you have making this film?”

“It’s just been Tina and I. That’s not by accident, that’s by design. I’ve spent most of my life making episodic television like the Highlander, Disney films and other US and Canadian TV. I’ve evolved out of that because I grew out of it and wanted to work on stuff that resonated and meant more to me. Moving into documentary, which is where I started, I chose to not go the route of what I’d been doing in Hollywood North. They typically use large crews and very short schedules. I chose to have a very small crew and very long schedules. For example, Haida Gwaii is just Tina and I. We could afford to spend months waiting for the sun to go down the right way or waiting for the tide to come in. I value the time much more than having to wait for a bunch of light trucks to line up. It’s wonderful to have that kind of freedom but that comes as a result of working a lifetime in the field and having the great opportunity to learn every single craft discipline. I’ve gripped films, I’ve gaffed films, composed music, been the editor on lots of films, I’ve shot films, been a sound recorder for years and all that stuff. There really are no disciplines in the craft that I’m not pretty consistent with. It takes a while to learn all of that but I’m very comfortable doing all of it, including building the computers that we edit on. It allows you that freedom to not have to depend to heavily on a big crew. I direct and produce. My wife Tina also produces. We co-edit, co-shoot and pretty much do everything. Kevin Eastwood is our Exec. Producer, Bill Shepard who mixes our sound and Gary Shaw who does all the video lab work down at Sun Street Post as well as the good folks down at Knowledge Network who work on the promotional side. That’s the team. We filmed for a year and a half and were there over two summers and went out on three separate trips.”

In the beginning of the film there is a lot of footage of the logging from companies that moved in to take all they could from the rich forest until restrictions were finally imposed. The damage had been done and the landscapes were changed forever. Charles explains further.

“The story is far from over and it’s a constant battle against the resource companies that want to extract the logs. They don’t have complete control of the land and not everyone is Haida Gwaiin’s. So many people that live there are like-minded progressive people and are appalled at over fishing and over logging. They’re a lot more conscious of it there and they fight harder, people are involved. That’s what makes it such an interesting story.”

“I was amazed at the flourishing population of the Archipelago given that its 100 miles off the west coast, but then it’s revealed in the film that tens of thousands of people died from smallpox in the 1800’s. Had that not happened do you believe it would still have a large population?”

“Absolutely! It was highly populated all over the entire Archipelago. The numbers really vary. There are Haida Gwaiin’s spread out across BC and Canada as well as parts of the US. People come and go from the Archipelago all the time because making a living there is not super easy and people leave to go onto school but they always come back. It’s like everyone knows each other there. You can’t walk down the side of the road because someone will offer you a ride. It’s such a close-knit community. Although times are changing, there’s still no big franchise on cell phones and people still take the time to talk to one another where other places with 21st Century technology may not.”

“How long does it take to get out to Haida Gwaii?”

“It all depends on which way you go. To canoe would take several months (chuckle) but to fly by plane is three hours. If you drive, you travel up to Prince Rupert which is a 14-16 hour drive followed by a 6 hr. ferry ride and then another short ferry ride to get to Queen Charlotte City. It’s not easy and it’s not cheap. Flying or driving can get fairly expensive.”

“How is tourism up there, considering it isn’t easy to get to?”

“Haida Gwaii is on more peoples bucket list than you can imagine. People will go there and say that they’ve been dreaming of going there their whole life. People from all over Germany or Japan will tend to travel there. It attracts a certain kind of person and not the kind that would go to Vegas or Club Med because they don’t have any of those services. There are no big fancy hotels with swimming pools or spas. There are hotels, BnB’s and some nice restaurants but otherwise it’s more what you’d expect in a logging area. For the progressive type that enjoys kayaking, mountain biking it’s a dream come true.”

“Has the film been screened in Haida Gwaii?”

“Oh yes, it’s been to Queen Charlotte which is the southern town and Massy, which is the northern town. It was wonderful; we went over with the Knowledge Network producers. When it screened, it got standing ovations. We were a little nervous at first but people really loved it.”

“I noticed that you had used a drone to capture many shots. It really added quite a spectacular birds eye view. That was an amazing idea to show the viewer so much more.”

“That was our very first drone and the learning curve was pretty steep but I never crashed it, it went pretty well. We wouldn’t have been able to capture the milky bloom in the water from the herring without it. However, I do find that drones are being terribly overused and becoming a bit of a gimmick because people use them for everything. To me, a drone is a crane or a helicopter. In a case where you’d use a helicopter, if you can use a drone it’s cheaper and safer. In the case where you need a crane, a drone is infinitely cheaper. They do have their drawbacks, such as control and interchangeable lenses, no control over aperture or a focal lens but for the stuff they’re good for they’re amazing. We’re on our third drone now and the technology keeps getting better. It’s also environmentally much more friendly. The environmental footprint of a helicopter is extremely high.”

“How long has the film been out there?”

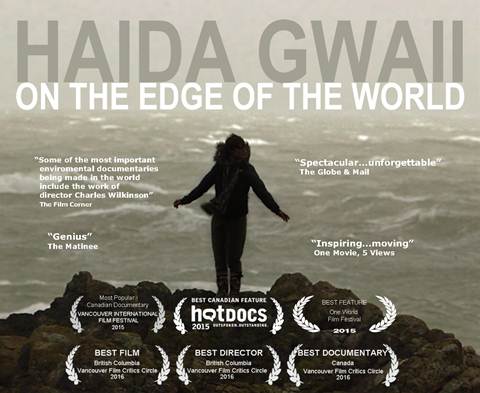

“It’s been close to two years. When we released it, we premiered it at Hot Docs and it won best feature movie. That was a huge boost and it later had a theatrical run after screening at more festivals. During its theatrical run it was the highest grossing Canadian film in theatre in Canada in 2016 and not just documentary but in Canadian film period per screen. People were lining up around the block at the Rio and Vancity for months to see the film. The same thing happened in Toronto at the Blue Rose. It really struck a chord with the audience and we’re pretty proud of that.”

“How did you finance the production?”

“It was funded through the Knowledge Network and the Canadian Media Fund. The real key is a proper business model. I used to raise financing over a million dollars for a film that would gross a few hundred thousand dollars. I finally realized it wasn’t a good business model. I spent years doing that and I won’t do it anymore. With one organization, there’s only one name on the poster. The money is much less but it’s enough to make a movie and turn a profit or break even. Documentaries are so popular now and it’s a real thrill to be making films where we can return that money. I’m very proud to be able to say that since film school I’ve been able to support myself and my family with money I’ve made strictly from film. I’ve also been pragmatic in that the movies you make have to make sense.”

“Where did you go to film school?”

“Simon Fraser, it was back in the day but I loved it. I did my post grad at UBC at the Film Center. I personally feel like everyone looking at film school should first work in the industry for a couple years first to find where their strengths and interests are.”

“Do you know what type of film you want to make next?”

“We’re already in production on our next feature documentary. It’s a story about an artist that changed the way we all live on the West Coast of North America. We’ve been shooting and editing already. It’s going really well. Documentaries are very different from making movies. It’s like playing a big game of Tetris but you have to invent the pieces you’re fitting together. Hopefully you find those pieces and put them together in the right order. It is super challenging at times and you wake up in the morning telling yourself you can’t do this, but then you keep working at it until it seems to work and it seems to keep going. If you really have something you’re trying to say, it becomes your beacon that guides you home. I really have a point to say about this one so I’m very optimistic.”

Charles continues;

“Most of the work I do is about the human condition and increasingly it’s about the environment. This story is very much a way of approaching our attitude toward the environment, the natural world, social justice and inequality. What makes this story so good is that it is an avenue into those themes. It’s not just a biopic about a guy that paints or carves; it’s about a cultural warrior and about the wars that we need to fight, so it’s pretty engaging.”

“Did your wife have a background in filmmaking before you met?”

“She did actually. Her dad was a very well known documentary filmmaker in Europe. He spent his whole life making hundreds of films before immigrating to Canada. I had met Tina’s brother in film school. His name is Tobias Shliessler and is one of the most sought after cinematographers in Hollywood. He shot Dream Girls, Friday Night Lights, Battleship, The Run Down, Beauty And The Beast. The list goes on and on. He’s doing very well and we’ve become very good friends. His dad was making films here and needed a soundman. Sound was my specialty so I began working for him recording sound and editing. It takes a special kind of person to understand film and the crazy hours you work and the fact that that’s the life you’ve chosen.”

“Where can people see Haida Gwaii – On The Edge Of The World?”

“It’s available on DVD and online at www.haidagwaiifilm.com. Or my own website at www.charleswilkinson.com. We have people from all around the world from Borneo to Romania buying it. We don’t sell them for a lot of money but it’s such a kick to see people from all over the world getting inspiration from Haida Gwaii. It also still screens all over the place.”

Haida Gwaii – On The Edge Of The World has recently screened at Vancity Theatre on Sept. 3rd as part of the Directors Guild Initiative Showcase of BC Directors. This film is remarkable in it’s ability to capture the essence of Haida Gwaii and it’s amazing inhabitants. If you still have room on your bucket list of destinations, watch the film. You will be glad you did.